“An honor and a privilege to have served as a keynote speaker at the inaugural FCLE conference held at FPT’s Can Tho campus. As a first-time visitor to Vietnam, the experience was all the more significant for me professionally and culturally. The conference theme, "Rethinking Pedagogical and Methodological Approaches to (Online) Language Teaching and Learning," embodies a genuine commitment to reforming and enhancing local English language teaching practices, as well as an earnest effort to achieve this through creating an international network of like-minded scholars and practitioners. The FCLE conference, meticulously programmed and effectively implemented by a dedicated and innovative team of organizers, provided attendees with an intellectually stimulating and culturally enriching experience that promises to have a lasting impact.”

ZhaoHong Han, Ph.D., Keynote Speaker FCLE 2024

Professor of Applied Linguistics

Director, Center for International Foreign Language Teacher Education (CIFLTE)

Teachers College, Columbia University

Box 66

525 W. 120th Street

New York, NY 10027

________________

“I was so impressed by the professionalism of the conference committee. The care, attention, and respect shown to me was beyond my expectations. I had a long conversation with Prof Dan Wessner before the dinner. I was telling him how this conference created a great imbalance in terms of giving and receiving, for me personally. What I was able to give as an “expert” was probably much less compared to what I received—the cultural experience, the learning, the exemplary care and attention, the hospitality. You helped me get rid of my sense of guilt about not visiting Vietnam earlier.

You have created a wonderful forum through this academic festival which can be nurtured for the future. I will be happy to be part of any collaborative efforts resulting from this event.

Thank you for making me indebted to you.”

Obaid Hamid, Keynote Speaker FCLE 2024

Associate Professor, School of Education

The University of Queensland, Australia

________________

“Thank you for welcoming me so warmly.

I am back at work and yet cannot forget how happy and honoured you and your team made me feel in Can Tho.

Congratulations! FCLE was definitely a success.”

Thanis Bunsom, Keynote Speaker FCLE 2024

Editor-in-Chief, rEFLections Journal

King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi, Thailand

________________

“It was a nice opportunity for me to attend the FCLE and listen to new ideas and inspiring research findings from our plenary speakers and participants. The FCLE organizers have worked effectively to facilitate the presenters as well as the listeners. Thanks a lot for your hospitality and support. I hope to see you all at FCLE 2025.”

Dr. Nguyen Van Huy

Vice-Rector, Hue University of Foreign Languages and International Studies

Hue City, Vietnam

________________

“Thank you very much for your warm welcome and care during the event. It was my honor and pleasure to collaborate with you and your team. FCLE 2024 gave the audience lots of food for thought, I believe. I do hope to have more opportunities to work with you in the future.”

Dr. Phan Thi Thanh Huyen

Acting Vice-Dean, Faculty of Foreign Languages, An Giang University

An Giang, Vietnam

________________

“Tôi xin chân thành gửi lời cảm ơn sâu sắc nhất tới quý Thầy, Cô, các bạn hỗ trợ vì đã tổ chức một hội thảo khoa học đầy ý nghĩa và thành công tốt đẹp. Sự chu đáo, tận tâm và chuyên nghiệp trong từng khâu của BTC đã tạo điều kiện thuận lợi tối đa cho tôi có cơ hội chia sẻ những hiểu biết ít ỏi của bản thân mình và tiếp nhận, mở rộng nhiều kiến thức mới. Qua hội thảo, tôi không chỉ học hỏi được nhiều điều mới mẻ mà còn cảm nhận được sự động viên, khích lệ và hỗ trợ nồng hậu từ phía Ban Tổ chức. Sự kiện này không chỉ là một diễn đàn khoa học mà còn là cầu nối quý báu giúp tôi được kết nối, hợp tác và phát triển trong tương lai. Một lần nữa, xin cảm ơn từ tận đáy lòng.”

Lê Đỗ Quyên, Presenter FCLE 2024

Nguyen Tat Thanh University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

_______________________________

Obaidul Hamid | Published: 00:00, Feb 10,2024

I WISHED to visit Vietnam out of a sense of epistemic guilt. At the start of my academic career in Australia, my postgraduate classes were numerically dominated by Vietnamese students. I also had the privilege of working with half a dozen Vietnamese PhD researchers as their principal supervisor. Together, we discussed many aspects of Vietnamese English language policy, pedagogy, and assessment at all levels of education. These Vietnamese scholars wrote more than a dozen journal articles and book chapters with me as their co-author. So, I was markedly engaged in knowledge-making about Vietnamese education and society. However, my knowledge of Vietnam was gained only from a distance. On occasions, I had an ethical angst that I was commenting on many aspects of Vietnamese society with no first-hand experience.

I worked out a plan to visit Vietnam in early 2020. I booked my flights to Cambodia to attend an annual conference, and I thought I would cross the border and spend some days in the south of Vietnam. However, that trip never took place, as the world was gripped by a pandemic.

In late 2023, when I received an invitation from the organisers of an English language conference at Vietnam’s FPT University, I couldn’t think of saying anything but, ‘Yes, I would love to attend the conference. Thank you very much.’ I remain grateful to this private university and the conference committee for their exceptional care, respect, and generosity. I had a brief but deep social and cultural immersion, and I would reflect on my learning for days and months. The trip also gave me a new kind of guilt. The organisers over-rewarded my modest contribution to the conference —socially, culturally, educationally, and materially.

I arrived at the airport in Ho Chi Minh City in the early morning of a January 2024 day. Officially, it was winter, but the temperature couldn’t have been less than 26 degrees Celsius. I was cordially welcomed by my main host, who was a former PhD scholar at the University of Queensland, Australia, where I teach. He must have started from his home around one a.m. to be at the airport by 5am. He dropped me off at my hotel in the centre of the city, shoving millions of Vietnamese Dong in my hands. He suggested I explore the city on my own until the following morning, when another colleague would accompany me to Can Tho City, where FPT University is located.

How would you feel being in the city of Uncle Ho, as the legendary Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh is lovingly and respectfully called? It reminds you, among many things, of the American-Vietnam war that is probably known everywhere in the world. It was not just the Americans who tried to mess with Vietnam and faced a shameful defeat. This country had attracted other imperial powers too — Chinese, French, Japanese, and Russian. From a language policy perspective, foreign languages in Vietnam are considered ‘barometers’ of its relationships with foreign powers. What foreign power was around could have been known from the language that was taught in the classroom.

My hotel was next to Central Park, where the colourful ‘Tet’ festival was underway as the city was preparing for the new year. I walked through the park, scanning the stalls, the people, and the goods and artefacts that were on display. It was a display of market capitalism, I judged. I wished to walk further into the surrounding areas, but my ignorance of the Vietnamese language prohibited me. Almost all road and shop signs were in Vietnamese with appropriated Roman scripts. It looks like English, but it is not, comparable to what I saw in Indonesia and Malaysia.

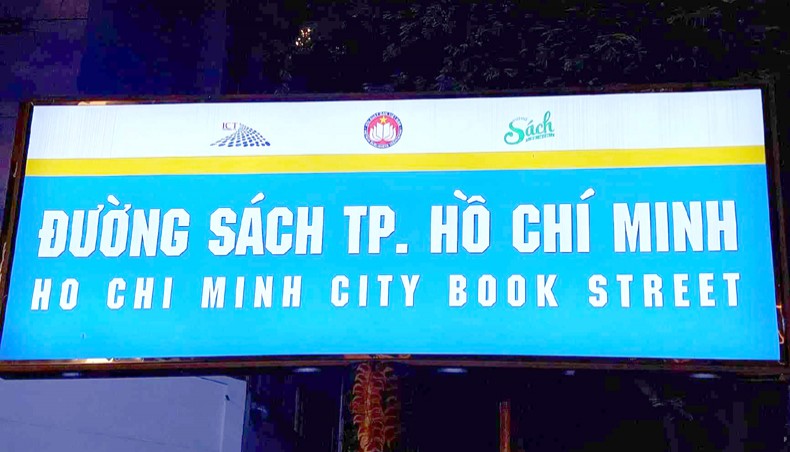

The winter day ended rather quickly. I googled restaurants for my dinner. Halal Saigon sounded interesting and was just over a kilometre away from my hotel. As I walked back along the footpath of the busy road with a full stomach, I was further entertained by the generous display of lights and colours all around. Every now and then, I found Westerners walking along, in singles or pairs. Almost halfway through my hotel, my eyes were caught by a sign that read, Ho Chi Minh City Book Street.

I turned left and entered the street almost by instinct. The entrance was decorated with different kinds of plants, giving it the look of a garden. The street is not for driving; you can only walk. As I walked further, I thought it was a reading place in the open. There were benches in the middle of the street where you could sit and read. There are also indoor spaces for reading. On one side of the road was a large café with many tables and chairs. You can order coffee and dive into the pages of whatever book you may be holding. Another indoor reading space had the shape of a bus; in fact, an unused bus was recycled. There were nicely decorated book shops on both sides of the street. Several art and craft shops added to its beauty and diversity. The street appeared to be a quiet, reading oasis in the middle of an urban jungle where sounds and noises were the norm.

The official name of the street is Nguyen Van Binh Book Street. It’s probably around 300 metres long and connects the busy Hai Ba Trung and the quieter Cong xa Paris streets. The impressive Notre Dame Cathedral is on one end, marking the legacy of French rule.

When I brought myself into the book street, it was rather quiet. I found several foreigners and a handful of locals. Eight in the evening was probably too late for a mid-weekday. I read on a tourist site on the Internet that the book street is visited by millions of Vietnamese and foreign travellers. It is rightly called ‘a paradise for bookworms.’ Some leading publishers in the country have their stores in this place. The Internet site notes that tourists can buy and read books, relax with coffee, and take photos in front of the bookstalls.

I was reminded of the Nilkhet book market in Dhaka, which perhaps has the largest collection of new and second-hand books in Bangladesh. The HCMC book street will be paler compared to the richness of Nilkhet. However, Nilkhet is only for buying books; it has no space for reading. Both places are important for cultivating readers, reading, and love for books. However, the HCMC book street has prioritised onsite reading and enjoying reading with coffee. Books and reading are made more attractive by adding an aesthetic dimension. The book street is also a tourist attraction where you can take photos. As a visitor, you would feel tempted to sit somewhere and read. At Nilkhet, you would buy your books and run away as quickly as you can.

Would it be too much to ask for some reading space in Dhaka?

Unfortunately, I couldn’t read a book over coffee in the HCMC book street. The book garden was an accidental discovery, and I had no time for it. I believe Vietnam will call me again, and I will not miss the chance of reading over coffee (or reaffeeing) next time.

I am sure you will do the same if you happen to be in Uncle Ho’s city.

Obaidul Hamid is an associate professor at the University of Queensland in Australia. He researches language, education, and society in the developing world.

_______________________________

Obaidul Hamid | Published: 00:00, Feb 24,2024

MY INTEREST in tourism was restricted to the language side of the global industry. As a language academic, I am keen on learning how language plays a role in this and many other sectors.

About half a dozen years ago, as I was waiting at the domestic airport in Dhaka to board my flight to Saidpur, I found myself sitting next to a young man in his early twenties. He was with a small group of tourists, also waiting for the same flight. He was tour-guiding them in North Bengal, where they were interested in something that I no longer remember. His eloquence in English attracted my attention.

We talked about the man’s education, his interest in tourism, and the nature of his work. I had many more questions to ask him, but the beauty of these chance meetings is that they come to an end rather unpredictably. We exchanged email addresses to keep in touch from a distance, but that hasn’t materialised.

In the meantime, my interest in tourism was further stimulated when I had a Bangladeshi scholar enrol in a PhD programme at the University of Queensland in early 2023. His thesis is probably the first PhD study to examine language in tourism in Bangladesh from a sustainability perspective.

Consequently, for every trip that I now have — whether within Australia and Bangladesh — or overseas, I wear multiple hats. Invariably, the trip will have an official purpose, an unofficial touristic opportunity, and an academic desire to seek the relevance of theories and ideas to tourist sites and stakeholders. The language question surfaces in all different ways, giving me unforgettable experiences.

In August 2023, I visited South Korea. I had the most luxurious bus ride of my life as I arrived in Daejeon from Incheon Airport in Seoul. However, I left behind my mobile phone on the bus, and it created communicative challenges for me as I was planning to hire a taxi from the bus stop to my hotel. Not surprisingly, I found my phone back the next day, thanks to the professionalism of the bus company.

In January 2024, as I was checking into a hotel in London Victoria, I was welcomed by a young woman. Her English was not extraordinary, but we got drawn to each other at a different level. I told her with some confidence that she was a Bangladeshi, but she corrected me. I never expected to see an Afghan woman in that place.

My most recent trip to Vietnam offered many opportunities to learn from touring. As I walked along the streets in Ho Chi Minh City, I was impressed by the presence of tourists who were walking, enjoying drinks, or hanging around. The sense of security that they must have been assured of by the host society is remarkable. This security must weigh heavier than linguistic security in the context of tourism.

My most memorable experiences were outside Ho Chi Minh City. As the taxi drove me and my Vietnamese colleague towards Can Tho City, where I was going to attend a conference, I felt like we were in Bangladesh. There were stretches of green paddy fields on both sides of the road. The vastness was occasionally punctuated by small collections of trees and dwellings here and there. As in Bangladesh, there were small shops on the roads selling snacks and other homemade products.

The conference organisers were a private university run by FPT Education. However, they had their eyes on promoting tourism on behalf of the country. They packed the whole conference programme in one day, scheduling ‘an experience day’ for the attendees the day before. We boarded a bus from the university campus at around sunrise, and we were headed to discover ‘the food bowl’ in the Mekong Delta region. Our first destination was a flower village in a small city called Sa Dec.

The flower village was a popular tourist attraction that was packed with people on a sunny day. It was a display of flowers and fruits in abundance. There were small lakes, walkways, and footbridges, all decorated with colourful flowers. There were places to sit, walk, take photos, and entertain yourself. The language question was almost immaterial compared to what was offered to me as a visitor.

Perhaps the most memorable event of the day trip was visiting a mandarin orchard in the city. There were many such farms of fruits and vegetables in the delta region. As we arrived at the main entrance of the orchard, we were served mandarins (we would call them oranges in Bangladesh) as we sat around tables. There were about a score of such tables where visitors were enjoying the fresh fruits. This is free, but you can also buy mandarins from them. I found it heart-filling to walk around hundreds of small trees that were turned yellow by the abundance of ripe mandarins.

The last leg of my trip took me to another southern province called An Giang, where I was sheltered at the university guest house. My host was a former PhD student and academic at the local university, who ensured that I felt completely at home in their hospitality. At the end of my work with the university, she arranged a day tour in which visiting a rain forest was the hallmark.

At all these tourist sites, I kept reflecting on the question of language. At a personal level, language is supposed to facilitate my consumption and cultural experiences. Academically, I was trying to measure the role of different languages — Vietnamese, English and my first language, Bangla (which was of course switched off during the trip). In most places, people used Vietnamese. The beehive keeper in the rain forest explained in his language how honey was produced. Similarly, as we were touring the forest on an engine boat, the boatman-tourist-guide was using Vietnamese to describe the biodiversity. Even when I shopped in one of the souvenir stores, it was Vietnamese that the shop assistants used.

However, nothing appeared unusual to me about this language. I didn’t understand what they said, but this did not prevent me from enjoying what was offered. It does not mean English does not have a place in Vietnam’s thriving tourism industry. The reception staff in the hotels spoke English; the conference was in English, and all my Vietnamese colleagues were excellent speakers and teachers of English.

Whether we talk about education, tourism, or governance, we need an ecological view of languages. A linguistic ecology may be dominated by certain languages, and this dominance is natural; other languages will be brought in, nurtured, and utilised as needed. An overdose of English may violate the ecology of languages and the eco-aspect of tourism in Vietnam, Bangladesh, or other non-Anglophone parts of the world.

The tourist encounter may also be an opportunity to cross our linguistic comfort zone and display linguistic creativity. The driver of the university in An Giang was supposed to drive me to the airport in Ho Chi Minh City at three in the morning on my last day. When he dropped me off at the guest house the night before, he reminded me of the start time of the ride, combining his limited stock of English with his non-verbal resources. Counting on his fingers, he said, ‘One, two, three, Ho Chi Minh City, go!’

To me, this was nothing short of a linguistic gem considering my interest in viewing English as a Southern language in the Global South.

Obaidul Hamid is an associate professor at the University of Queensland in Australia. He researches language, education, and society in the developing world.

_______________________________